Need of anonymity I. - How to rock privacy

The recent decades speeded up, twisted and completely changed the world. Modern technology not only reshaped the societies we live in, but it also undetectably pervaded our everyday life to change our ways of thinking.

If you are an average smartphone user you probably downloaded around 10 to 100 app in the past few weeks, to track your workout performance, record your spending, manage photos, follow the most important happenings in your network, kill time with the latest (and coolest) game and so on. This is just a single device of those you are using. Significant information we give out on where we are, what we do and what we probably think are accessible today for many parties, and in addition, we often voluntarily provide supplement to data being collected

This process could be described from many aspects. However, the overview of web tracking techniques makes an outstanding example on how the profiling based market extended tremendously over the years (e.g., behavioral profiling), and how conscious webizens engaged trackers in a seemingly never ending circulation: finding the way to avoid tracking and discovering new tracking mechanisms.

Suggested post: Fingerprinting @Tresorit blog

While general concern for online privacy was continuously growing, recently leaked NSA documentation revealing world-wide wholesale surveillance gave a boost to the rise of awareness. Despite the fact that we arrived to a positive landmark, there are still several white spots on the map of privacy and yet many false-beliefs surrounding the topic.

I have nothing to hide – why should I care?

There are several typical phrases denying the need for privacy that often emerges from the media. Probably the most frequently used one states that “if you have nothing to hide, you should be not worried” (and similar ones with different wordings). Eric Schmidt is also famous for quoting this, while now he yet seems to be seeking privacy himself.

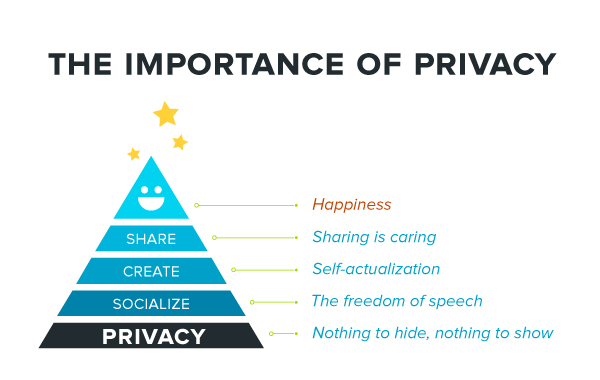

First of all: is privacy about hiding something? Definitely not. Bruce Schneier gives a few good counterexamples such as the need to “seek out private places for reflection or conversation”, “sing in the privacy of the shower”. We could think of sharing moments with the ones we love, or seeking loneliness to find ourselves. There are several other private moments in everyday life to choose from.

Privacy is also important as a basis for the freedom of speech. Dictatorships in the twentieth century showed us that if privacy is omitted (e.g., by allowing targeted surveillance on people disagreeing with the system), this will react in changing individual behavior and public speech. By looking it this way, we can see how privacy means freedom, why it is a basic human need.

Beside some level of secrecy, privacy is also includes control for disclosure among several other things (e.g., “my house my castle”). Daniel Solove quotes pretty good replies from his readers to the misunderstanding in question:

- My response is “So do you have curtains?” or “Can I see your credit-card bills for the last year?”

- So my response to the “If you have nothing to hide … ” argument is simply, “I don’t need to justify my position. You need to justify yours. Come back with a warrant.”

- I don’t have anything to hide. But I don’t have anything I feel like showing you, either.

- If you have nothing to hide, then you don’t have a life.

- It’s not about having anything to hide, it’s about things not being anyone else’s business.

Another problem that such an attitude can justify uncontrolled surveillance. If information is collected without a defined purpose, it can be easily abused. Definition of what is good or wrong can change over time, and what was once collected can be even used to condemn data subjects if it is in the interests of the currently governing forces. This implies several other questions. What data would be stored on you and for how long? Who could access it and make copies of it?

In addition, mistakes can happen anytime. For example, your financial records can look misleadingly suspicious, sufficiently convincing for the tax office to investigate you. Or your data can be leaked accidentally or hacked. In this case, how could you tell what is out there in the public? What is once out there, it stays there.

There are other public voices stating that we don’t care about privacy anymore or don’t simply need it in the digitalized age we live in. However, research shows that even new generations do care about privacy, though for them privacy is more about control. This might be unexpected regarding the strong influence of new technology on their lives, and propaganda of technology companies trying to have the young generation more engaged with their products (not surprisingly: most of their business models rely on controlling vast amount of user-related data).

We got a little enthusiast on the topic, so by end of the process we found a [tltr] alert flashing over the post. This is why we break this down to two pieces. The second will follow in some days. We reward your patience, by adding a super useful e-book on privacy, with many tips and tricks. Stay tuned, it is going to be great!